Hutong alleys: the soul of Old Beijing

Hutongs are special places unique to the city center of Beijing: these are the ancient narrow lanes that for centuries, together with the siheyuan (the traditional courtyard houses of this part of China), have formed the urban fabric of the city.

Back in ancient times, Beijing was a totally different city from any other in the world, especially compared with the big cities of the West.

In fact, most of the ancient cities and towns that have survived until today have grown naturally and somewhat spontaneously over the centuries in large part, but not Beijing.

Inside its city walls, Beijing was a carefully designed city, down to its houses, which follow those set and almost magic principles of Chinese urbanism and architecture which remained immutable for centuries, immutable as the Chinese society and the Imperial power who inhabited the city for almost one thousand years.

The capital was meant to be built according to a scheme that symbolizes the aspiration of order, balance, and harmony, which are the cornerstones of Chinese civilization.

The hutong alleys and the siheyuan courtyard houses were the urban spine of this system.

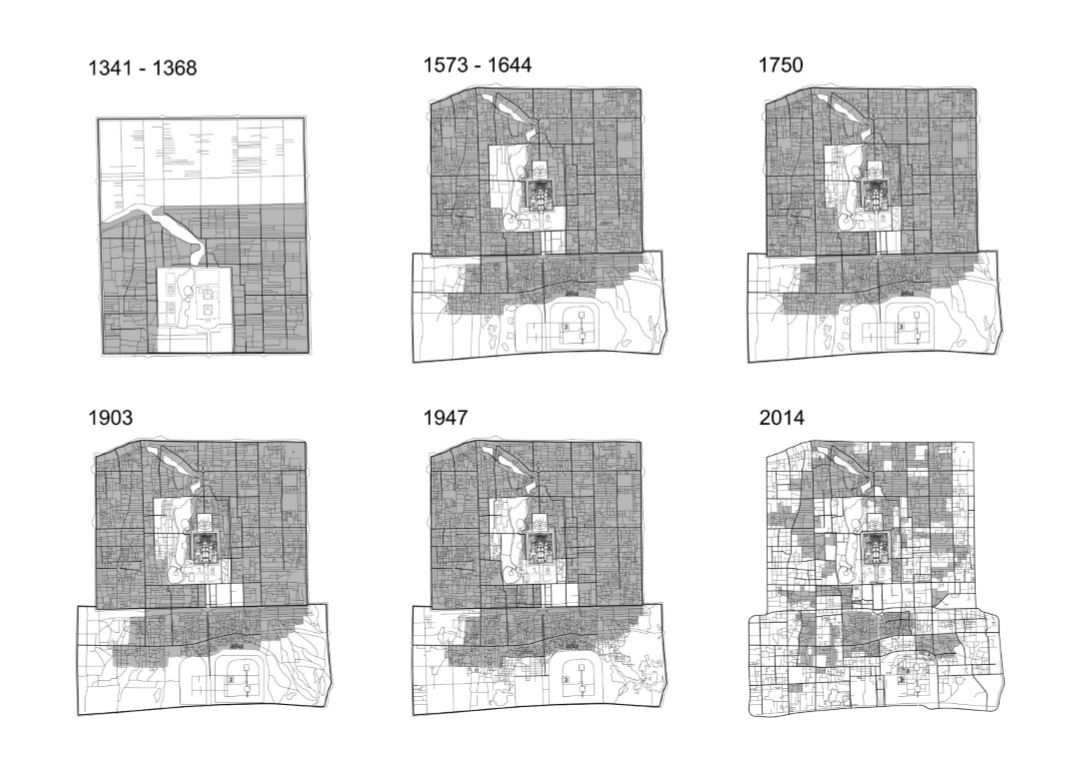

The hutong’s alleys are therefore really old: the term “hutong” appears for the first time in Yuan’s dynasty records (1267 – 1369).

In old Beijing, hutongs used to be “as many as the hair of an ox,” old chronicles says. Today, there are just a few hundred left, placed under a special conservation plan, which still sometimes doesn’t prevent their sudden demolition.

Recognized by many local people (especially the older generations) as the real home of the capital’s folk culture, nobody can say they truly experienced Beijing without exploring what is left of the old hutong neighborhoods.

It is quite fascinating to think that the oldest hutongs have been there for almost 600 years, and many of their paths never really changed since the foundation of Beijing.

The most ancient hutong neighborhoods are localized in the central districts of Dongcheng and Xicheng, in the area today inside the Second ring road.

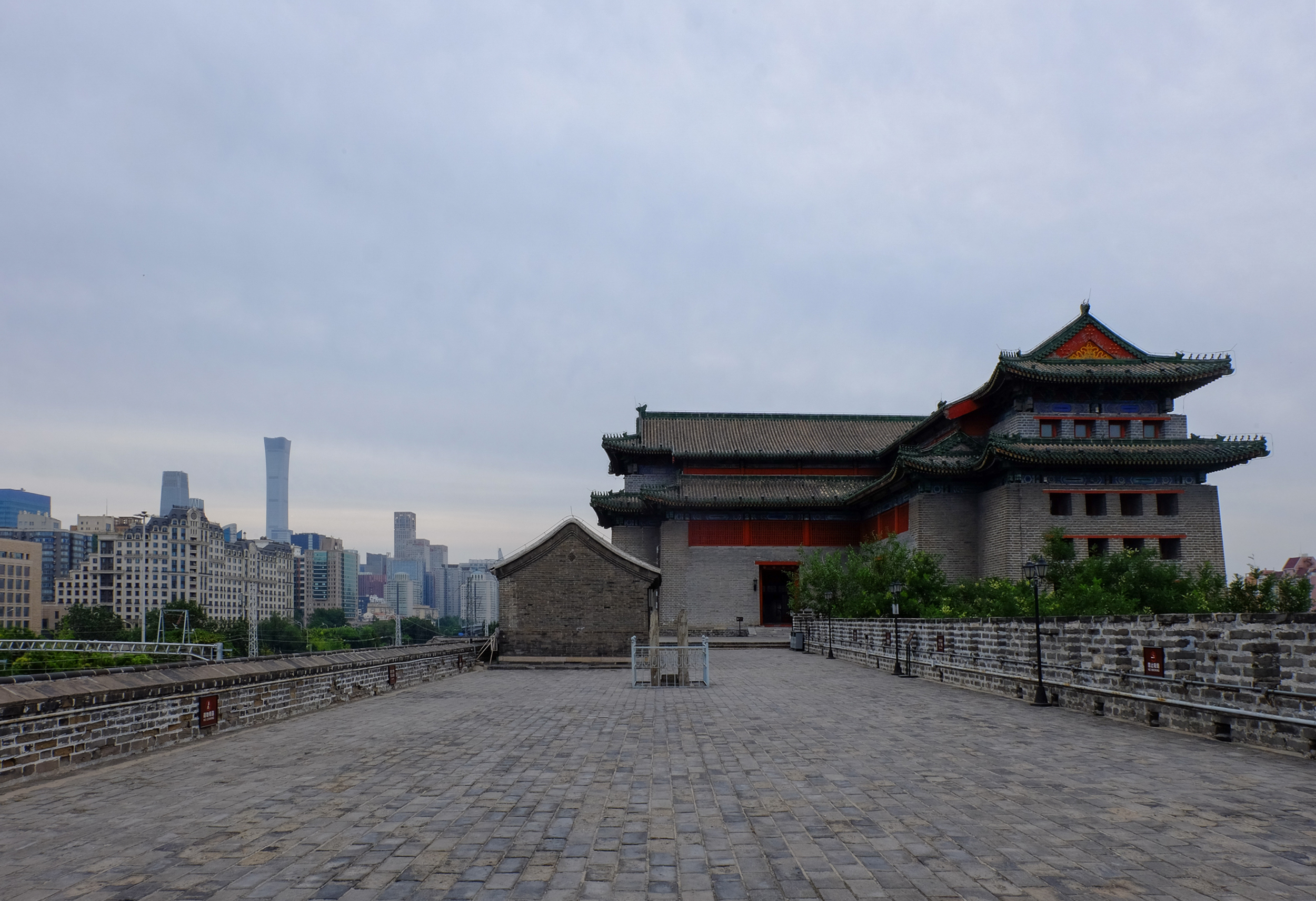

The Second ring road runs along the path left empty by the demolition of the City Walls, which enclosed Beijing since the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644).

For centuries, Beijing was a flat city made entirely of hutong lanes and one story high courtyard houses, with only a few taller landmark buildings or pagodas here and there, enclosed by over 12 meter high walls, barbicans, moats, and watchtowers.

Several demolitions and adjustments to the City Walls were made after the fall of the Qing Dinasty (1919), aiming to improve the road system and accommodate a modern railway system inside the fortified city.

But in the late ‘50s during the Cultural Revolution, Mao Zedong decided to complete the demolition process of the dilapidated remains of the City Walls, which at that time constituted a barrier for the expansion and development of the city.

A city wide demolition process that targeted the ancient buildings in the name of progress began, and forever changed the historical city fabric.

Prior to that in Beijing, the only architectural typology was the courtyard, used for every type of construction: common folk houses, markets, temples, and the Imperial Palace, with the main difference being the scale of the architecture, and the grandeur of the ornaments and decorations.

Just a portion of those ancient hutong blocks and courtyard houses made it to the present day, localized in the very center of the city and now under a special yet precarious protection.

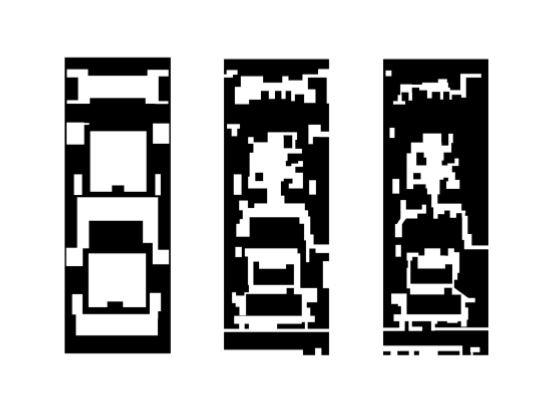

A traditional hutong block sees one courtyard house joined wall to wall with the next one, and so on and so forth, forming entire blocks crossed by the hutong lanes.

Originally the hutong lanes were entirely walled narrow streets, whose only opening were the gates (sometimes majestic, sometimes more modest) of the courtyard houses.

The houses were intended to host 3 generations of the family, all happily living together, sheltered from the outside by the external walls of the house.

Built in hutong blocks, Old Beijing was indeed a compartmentalized city, whose main streets features were walls and gates.

Many hutongs were also shaded by several big trees, planted at the side of the street or inside the courtyards. Some of those secular trees are part of Old Beijing’s treasures, under protection together with the houses.

With the Cultural Revolution that China experienced beginning in 1949, the urban pattern inside the second ring road started to drastically change. When Beijing became the capital of the People’s Republic of China (1949), the planned modernization naturally conflicted with the old city fabric, which for centuries regenerated itself constantly, but never changed its shape or pattern.

In the proceeding decades, under the reformist push of Mao Zedong, a huge number of people moved from the countryside to Beijing, as many new factories were constructed in the city center.

This caused a housing shortage that was partially handled by relocating the new urban immigrants in the siheyuan courtyard houses, that were in great condition at that time and owned by single families for centuries.

Starting from those years, the courtyard houses got fractionated, and several families started to live all together in the space once occupied by one family.

At the same time, together with the new factories, lots of new ‘modern’ residential complexes for the new working class were built in the city center, forever erasing entire hutong neighborhoods.

The situation worsened with the tremendous earthquake of Tanshan in 1976 in the nearby Hebei Province. Hundreds of thousands of homeless families were relocated in “refugee shelters” in the already crowded courtyard houses of Beijing. These shelters became a permanent part of the siheyuan houses until today.

Having been single-family homes for centuries, in the late 70’s the siheyuan began hosting up to 7-10 families. Consequently, this brought a drastic fragmentation of the ancient courtyards homes, now occupied by entire families living in one room. Many doors and windows were then opened, drastically changing the appearance of the hutongs. But the biggest change was the filling of the yards, often with makeshift constructions, in order to add living space. Many of the open spaces of the courtyard house became built up by 90%. The courtyard houses didn’t have a courtyard anymore.

The residents of the hutong had to give up their spacious homes, losing their privacy to embrace a new kind of local lifestyle, characterized by the almost absolute sharing of spaces, with the appropriation of public space for daily chores.

On the other hand, the lack of space and privacy generated the strongest social relations between the neighborhood community.

This peculiar and strong social life, born from necessity and discomfort, is what makes the hutong a unique environment today in the center of one of the most wannabe-futuristic cities of the world.

From the early 1990s, the city center fell into the hands of many real estate companies, which didn’t care too much for the heritage of the ancient, decadent old city. Without the existence of strict regulations to protect the cultural heritage of the courtyard houses, entire portions of the old urban pattern were wiped away, giving space to new high-rise residential and business districts, shopping malls, and wide roads, forever erasing thousands of hutongs and traditional siheyuan.

The irreversible damage was partially halted in 2003 with the drafting of a protection plan for 25 areas which survived the massive hutong destruction. By that time, a huge number of academic and literates desperately called for an action to stop the destruction of the old city pattern and its traditional lifestyles. What remained of the courtyard houses and the hutong street culture is in fact one of Beijing’s most important cultural heritages.

Destroying the hutongs means killing a part of Beijing’s soul; not only destroying the architectural typology –the siheyuan– that for centuries was the home of the Beijing population.

Destroying the hutong means destroying a half century of unique local culture, where the people had to give up their comfort, but gained the strongest communal life.

And the strong sense of community is what makes the elderly residents reluctant to leave when relocated in modern and more comfortable high-rise buildings somewhere in the outskirts of the city.

Even if now those 25 areas (later extended to 30) are under protection, this doesn’t stop the hutongs and the siheyuan houses from being constantly changed, demolished, and rebuilt.

It must be said that many old existing hutongs still struggle to adapt to the needs of a modern city, suffering from overcrowding, lacking the appropriate sewer system and private toilets and showers, parking spots, fire prevention measures, and legal licenses for many local businesses that spontaneously pop out.

The chance of being cleared and relocated in the suburbs within a few days notice and no possibility to object, discourages the inhabitants from investing in durable and good quality constructions, perpetuating the state of dilapidation.

Meanwhile the ancient urban tissue never stops changing.

Sometimes it is the inhabitants themselves who spontaneously demolish and rebuild their spaces. Other times demolitions and reconstructions are imposed by the government, aiming to clean up the messy and overcrowded hutong’s appearance, closing openings, demolishing illegal additions, and retouching the facades, adding some picturesque ancient flavor.

Because even if these ancient neighborhoods are now under protection, buildings can actually still be demolished and rebuilt, as long as they keep the traditional typology and appearance.

Within a few days, the urban tissue is wounded and healed, and in this way the old city continues to regenerate itself.

One of the best qualities of the hutongs is the human scale, which is not always granted in Beijing. The way to experience the hutongs is to walk or bike, as there is not enough space for cars to comfortably pass without clogging the entire lane.

In the hutongs, people meet, stop, and chat. The old inhabitants bring their chairs outside the old gates of the siheyuan and sit there for hours, drinking tea, and simply passing the time.

On warm days or summer nights many old men sit on small stools on the road to play chess. Those tournaments can get quite intense, gathering a large number of neighbors or passerbys who get caught up in the match for hours. Families play badminton in the street. Sometimes they dine outside, grilling some barbecue skewers. When the sun goes down, elderly women meet and dance together where the sidewalk is wider, sometimes waving colorful fans to pumping techno music, sometimes slow dancing in couples (practices that have been discouraged by the city government in an attempt to establish some public order).

The elderly take their animals for a walk or a ride, be they little dogs or caged birds.

You can find everything at the side of a hutong lane. Entire collections of decrepit and ramshackle bicycles, tricycles, carts, tuk-tuks, or electric scooters. Piles of whatever don’t fit inside the old courtyards. Wardrobes with lockers, old broken fridges, or air conditioners. Tables, chairs, or any type of furniture, fixed with chains not to be taken away, because everything that is left unattended (and still looks decent) in a hutong can be found by a new owner very quickly. Flowerpots, baskets. Laundry is drying everywhere, hanging from light poles. There is no a real line between public and private, if there is space, that space will not be wasted.

Walking through a hutong, visitors can find messy greengrocers alternating with small local shops for basic necessities, where a little bit of everything can be found. The next building maybe hosts a small sophisticated bar, or a quite expensive coffee shop. Then the ying-yang sign outside a door marks the studio of a fortune-teller. Next to it, a tiny baozi shop, where piles of steaming dumpling baskets are cooked before dawn, ready for the breakfast of the early morning workers.

Suddenly, a beautifully painted Chinese gate, locked. It may enclose one of the few preserved or renovated siheyuan houses, whose rich owner family can still enjoy their own private courtyard. They may even own a private garage (a true luxury in an environment where parking space is a real issue).

Sometimes entire hutongs are refurbished or rebuilt with new siheyuan houses displaying the finest traditional style, now affordable only to movie stars.

Gentrification is indeed a recent problem of the central hutong areas. The renovated or newly constructed courtyard houses, built in one of the most expensive lands of the whole country, far exceeds the budget of the majority of the local inhabitants.

Some other times gentrification is also happening through the commercial development of many hutongs, especially in the neighborhoods around Gulou and Houhai Lake.

Dilapidated hutongs became part of the government’s development plans, turning into shopping streets (to mention the most famous: Nanluoguxiang, which in 2006 was completely transformed from a very laid back local alley into a bustling and overcrowded tourist attraction, as a part of the face lifting plan of Beijing for the 2008 Olympics).

Dozens of food and coffee chains, western restaurants, clothes and souvenir shops, and bars are populating the hutongs of these areas, creating a tension between the growing tourist demand and the local ecosystem, a process that sometimes triggers the need to “clean up” the surroundings.

I have to make a confession, if it wasn’t already quite clear: hutongs are one of the places I love the most in Beijing, and this is the reason why I decided to live in a hutong house for all my time in the city.

Many Chinese friends ask me why I like it so much, and why so many foreigners seem to be keen on living in this kind of neighborhoods, since hutong life can be rough sometimes, compared to living in a flat.

I must admit, my life is not always comfortable.

I live in a fraction of an old traditional siheyuan courtyard house, which has been split into 5 households.

In winter the house tends to be very cold because of the really poor insulation of my wooden door and windows, a problem that I solved by getting creative with plastic wrapping.

In summer my house is quite enjoyable, except when it rains a lot, because the rain leaks through the kitchen ceiling, and no matter how many times the landlord tried to fix it over the years, it still leaks.

I can go on and on with all the things that are not completely right in my house (which are quite a few…), as my small hutong studio has just been partially adjusted to some more comfortable life standards and is not one of the fancily renovated ones (even though I am one of those lucky people which own a private bathroom).

But despite the few usual hassles that anyone has to go through when consciously deciding to live in such a kind of house, I like my life there so much that all the discomforts are easily overcome.

When I talk about my house, so many people don’t get why I like it so much. I wouldn’t have these kinds of issues if I was living in an apartment. And this explains why many of the younger generations born in hutongs prefer to move into modern apartment buildings, which are so much more hassle-free.

What I like about living in the hutongs is the human centered lifestyle and the feeling of being close to people.

Hutongs are indeed very quiet and friendly, preserving a comfortable environment for the human scale, in contrast with many of the dense, futuristic, and sometimes alienating districts of the modern part of the city.

The relationship between me and my neighbors is quite different from the one I would have living in an apartment.

The way the space is divided and occupied makes it so that I have to pass through my neighbors stuff, smell what they are cooking, meet and greet them to reach my private home. We are always around each others (being this a good thing… or a bad thing).

There is definitely a lack of privacy going on, which gets redeemed on the other hand by the feeling of safety and not being alone.

And I can just imagine how strong this community feeling can get after decades of living literally in the same little courtyard.

Hutongs are hard to understand and even harder to explain, and I am not sure I completely managed to do that despite all my effort. There is too much going on.

At a first glance, it is hard to grasp the crazy yet subtle juxtaposition going on in what’s left of these unique ancient neighborhoods. A juxtaposition between old and new, rich and poor, traditional and modern, original and fake; there is something extremely peculiar about modern China.

Too many layers, and so different between them, which makes it easy to judge and impossible to make a totally objective conclusion which takes into consideration every aspect of it.

It is painful to witness the demolition of entire hutongs, with the local shops bricked up and the houses torn apart, ignoring the fact that many of those constructions where illegal, not obeying to safety regulations and healthy living standards.

As an outsider like me, it is easy to fall in love with the rough and unpolished hutong life, forgetting the fact that in some poorer neighborhood a public toilet in a hutong is shared by an average of 70 families which don’t own a private bathroom, and the situation inside the most crowded courtyards sometimes resemble a slum, contrasting the image that Beijing is trying to give it to itself, as the Capital of one of the superpowers of the world.

Hutongs are one of the most valuable and delicate parts of Beijing for all the things they stand for: the memory and the heritage of a glorious secular past, what remains of decades of local culture born from the years of the Cultural Revolutions, and the extreme challenge to adapt to the modern capital city that stands just few hundreds meters away, at the other side of the second ring road.

I believe that the identity of the city cannot be fully understood without exploring the hutongs: the beautiful mess resulting from the charming, unpolished and precarious lifestyle of the hutongs is one of the most precious treasures of Old Beijing.

You may also like

stay tuned !

search for a destination

latest travel itineraries

latest CHINA articles

Text and pictures by Architecture on the Road ©

Architecture on the Road

All rights reserved

All photographs on this site were taken and are owned by me (unless credited otherwise).

If you would like to use some of these photos for editorial or commercial purposes, many of these are available on Shutterstock (click the link below). Otherwise, please contact me on Instagram, Facebook, or by email.

Do not use my pictures without my written consent. Thank you!