DIKENGYUAN: SUNKEN COURTYARD HOUSES FROM THE LOESS PLATEAU

The Loess Plateau, which extends to the north of China through the provinces of Shanxi, Shaanxi, Gansu, Ningxia and Henan, boasts one of the most interesting vernacular architectural typologies of the country: the Yaodong (窑洞), or “cave houses”.

It is estimated that over 30 million people still live in Yaodong dwellings in northern China. This kind of building is in fact very practical: the living spaces are dug into the earth or the rock of the plateau and are characterized by very thick walls and a vaulted ceiling. Warm in winter and cool in summer, this type of dwelling does not require special materials for the construction, just the earth of the Loess Plateau itself, and as such it is very cheap to construct and maintain.

There are 3 different types of Yaodong, which vary depending on the condition of the terrain:

– Cave dwellings dug in cliffs (靠崖窑 – kàoyáyá): usually built along the slopes and the cliffs of mountains and can be several stories high

– Sunken courtyard houses (地坑院; pinyin: dìkēngyuan): the rooms are excavated to form a sunken courtyard dug in the ground

– Stand alone cave dwellings (箍窑: gūyáo): the structure of the house is not dug or excavated, but stands above ground as an independent building. The inner space maintains the vaulted structure, achieved using bricks or stone to build the arches. The space between the arched structures is filled with earth

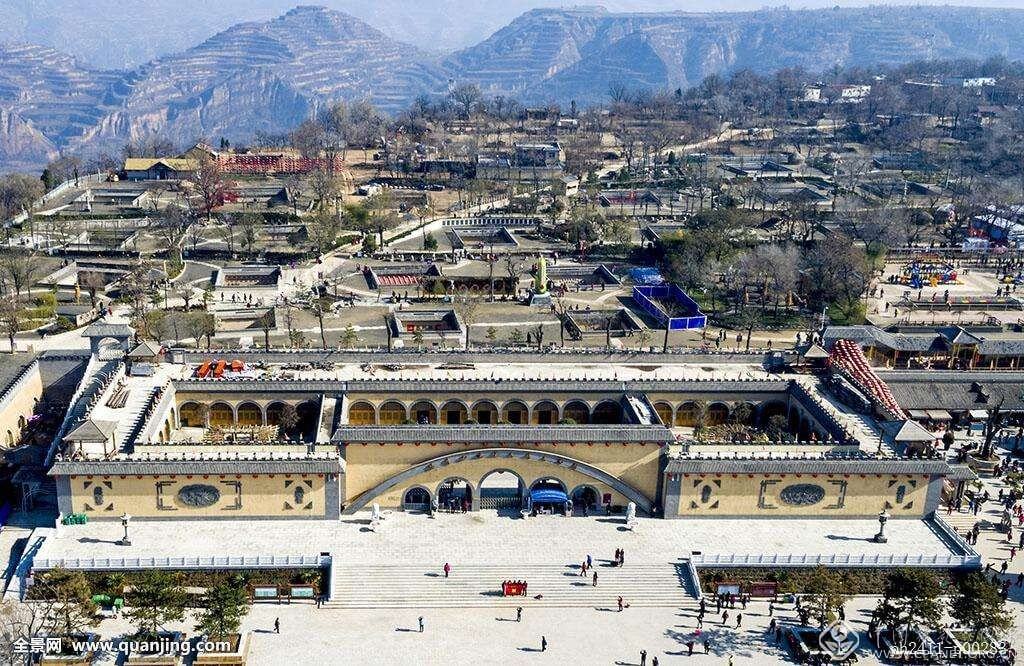

For my trip, I decided to visit the Dikengyuan kind of cave houses, which are scattered in the countryside around the city of Sanmenxia in the Henan Province. Sanmenxia is a modern city of modest size located in the southern part of the Loess plateau. In the countryside south of Sanmenxia nestled among the orchards, there are many small villages, whose main architectural typology is the Dikengyuan.

Much of the time I spent looking for Dikengyuan houses was spent in the village of Qucun (曲 村), one of the most developed and well-maintained Dikengyuan agglomerations, where it is possible to admire dozens of these pit-like courtyards of different size and quality, some of which are still inhabited.

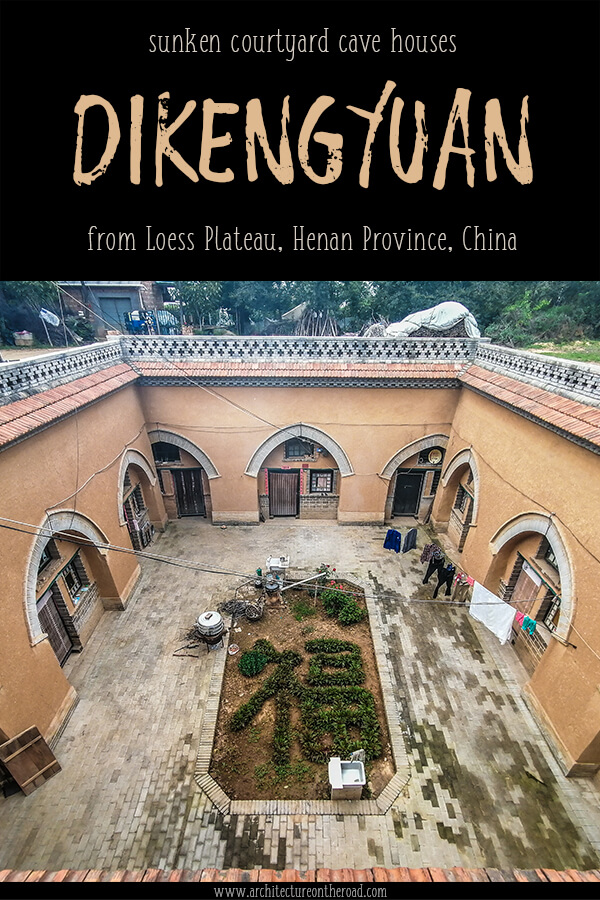

The Dikengyuang (translated literally: “pit courtyards”) houses develop around a courtyard dug into the ground.

The four sides of the courtyard are the four outer walls of the dwelling, which opens up to all the rooms of the house; The courtyard is therefore the only source of natural light.

The interior rooms have a rectangular plan and an arched ceiling structure, a conformation that reflects the Chinese concept of “round sky and square earth”.

The courtyard can vary in size and proportion, although it usually groups 3 rooms one next to the other along the same side.

Usually the external walls are covered with rammed earth.

The access to the dikengyuan is characterized by a sunken slope dug in the terrain that leads down to the underground dwelling door.

Walking through Qucun, we got to admire the courtyards of dozens of Dikengyuan from above, some of which are still uninhabited today. Many of the younger generations have moved to the city to work, while some of the elderly inhabitants prefer to live in more modern and comfortable buildings built above ground overlooking the pit courtyards.

It should in fact be said that the Dikengyuan are a very simple and cheap type of dwelling, developed in primitive times. Although they guarantee excellent climate comfort thanks to the thickness of the walls, they do not offer or allow the installation of many other modern facilities.

The inhabitants of the Dikengyuan welcomed us warmly and with curiosity. They turned out to be very hospitable and willing to open their doors and talk about their homes and lifestyle (knowledge of Chinese is essential), happy with the attention we showed to the local culture.

After the exploration of Qucun, passing through peach and pear trees, we reached to the near village of Caocun (曹 村). This second village stretches along the slopes of a canyon (clumsily mistaken for a mountain on google maps during the journey planning phase).

Caocun looks much poorer than Qucun. The Dikengyuan houses of this village are in fact smaller in size, the decorations less refined (some of them are completely raw) and many courtyards are in a state of neglect and disrepair.

Carrying several kilos of peaches kindly given to us by every villager we encountered along the way, we returned to our guesthouse in Qucun at sunset. Some of the most beautiful and spacious Dikengyuan are home to restaurants and rooms where you can spend the night. It is in one of these Dikengyuan, open to the public, that we received the warmest hospitality from the owners, who despite the language barriers made us feel part of the family.

The city of Sanmenxia is well connected by train to the main cities of China and the province of Henan. Thanks to the high speed railway, reaching Sanmenxia by train from Beijing takes only 3h, while from Luoyang and Zhengzhou (the biggest and more popular destinations of Henan Province), it is only 30 minutes.

From Sanmenxia South Railway Station (where most of the fast trains depart), it is possible to get a taxi ride to Qucun. The village is 20 km South of the city, and the ride takes around 30 minutes. The fare we payed was 60 rmb, which is probably more expensive than the right taximeter fare (but our driver clearly told us that we wanted to go far out from the city and he clearly had no intention to use the taximeter for that…).

Beware that 10 km in the direction of Qucun there is a huge Dikengyuan compound called Shanzhou Dikengyuan (陕州地坑院), which is a kind of newly built museum of Dikengyuan typology. Since this is one of the main touristic attractions of the county, most drivers will probably assume that this is where you want to go. So did our driver, who brought us there first, even if we told him from the beginning that we wanted to go to Qucun village, pointing to the place on a map and showing the GPS coordinates. After he brought us to the entrance of the museum, we refused to get of the taxi, explaining that we wanted to see the real homes of the people. Eventually we managed to reach Qucun village, which is just 15 minutes drive from the museum .

We also kept in contact with the driver, and he agreed to come to pick us up the following day to bring us back to Sanmenxia.

The visit to this village turned out to be a wonderful experience from an architectural, cultural, and human point of view.

When organizing the trip, I found it hard to find information on how and where to see these houses, and frankly I am surprised by the lack of attention given to this destination compared to other kinds of Chinese vernacular dwellings.

The Dikengyuan architectural typology is really interesting and unique, and should not to be forgotten!

From the human point of view, the inhabitants of the Dikengyuan gave us the warmest welcome, showering us with the fruits of their trees, showing us their homes, and were genuinely pleased by our interest in their lifestyle. This is a kind of curious and sweet hospitality that I often encounter while traveling in remote places of the Chinese countryside.

The visit to Qucun to discover the Dikengyuan, a trip that I postponed for months, turned out to be a really precious day that I will never forget.

Pin it on Pinterest!

IF YOU FOUND THIS POST INTERESTING AND INSPIRING, HELP ME TO SHARE IT WITH OTHER TRAVELERS!

You may also like

FRom the same province

stay tuned !

search for a destination

latest travel itineraries

latest CHINA articles

Text and pictures by

Architecture on the Road ©

Architecture on the Road

All rights reserved

All photographs on this site were taken and are owned by me (unless credited otherwise).

If you would like to use some of these photos for editorial or commercial purposes, many of these are available on Shutterstock (click the link below). Otherwise, please contact me on Instagram, Facebook, or by email.

Do not use my pictures without my written consent. Thank you!